Can Memory Games Actually Help You Learn? What the Science Says

Are memory games actually helping you learn — or are they just digital distractions in disguise? If you've ever used CortexQuest or similar memory-matching games to learn vocabulary or science concepts, you've probably asked yourself this.

The short answer: yes, memory games can help with learning — but they're not miracle brain boosters. Research from psychology and neuroscience shows they work best when used strategically, not passively.

Let's explore what the science says about how memory games affect learning, what they can and can't do, and how to use them effectively.

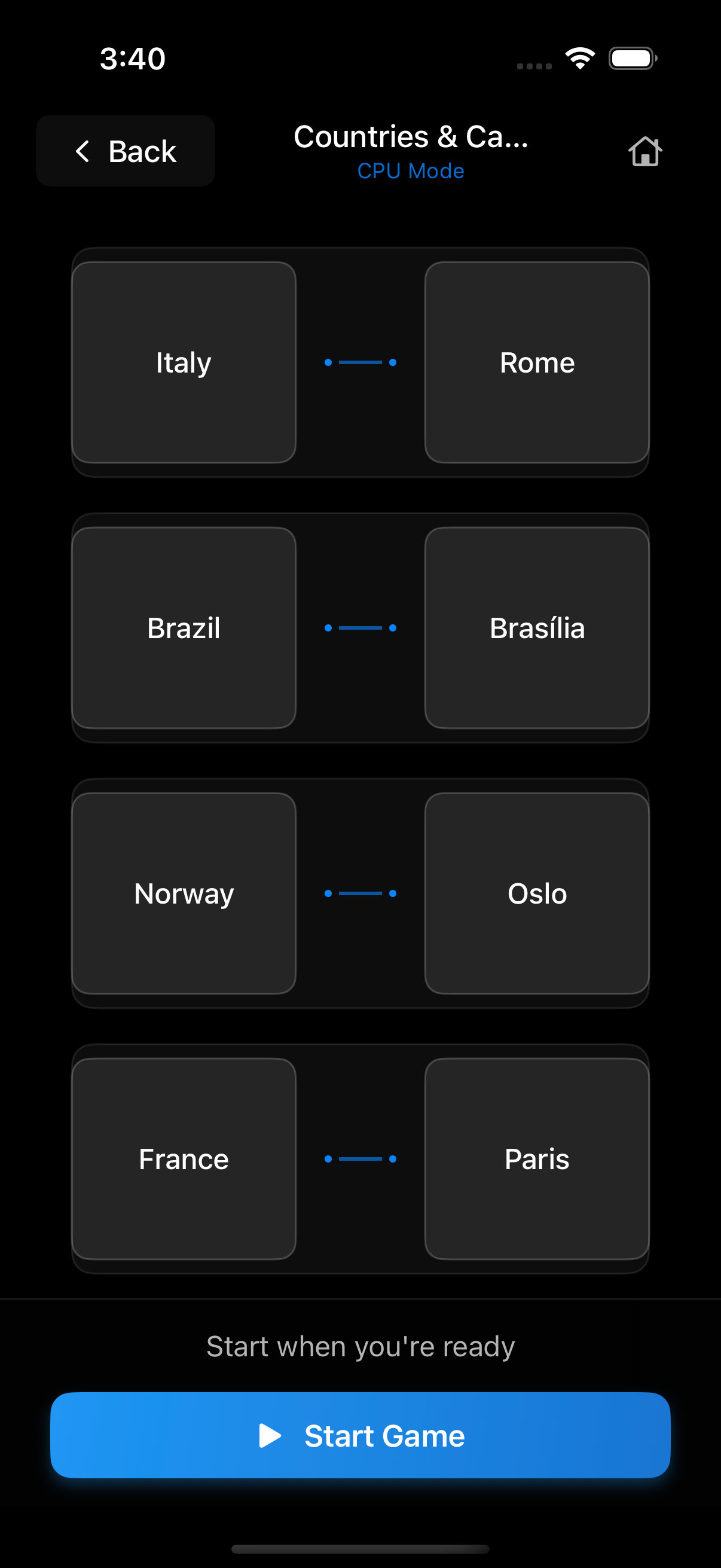

CortexQuest's game setup screen showing pairs before you start playing

The Big Picture: What Memory Games Actually Do

They Help with Specific Learning

Memory games can help you retain specific facts, such as vocabulary, definitions, or science terms — especially when they involve active recall and spaced repetition.

They Don't Make You Smarter Overall

There's little evidence that memory games increase general intelligence, boost IQ, or significantly improve unrelated cognitive skills.

The Myth of "Brain Training"

In 2014, more than 70 neuroscientists signed a public statement warning against inflated claims about brain-training games. The key finding?

"Playing memory games makes you better at memory games — not necessarily at life."

This "transfer problem" — improving at one task without affecting other skills — has been confirmed in major reviews (Simons et al., 2016).

But that doesn't mean memory games are useless. In fact, when used correctly, they leverage some of the most powerful learning principles in cognitive psychology.

4 Science-Backed Learning Benefits of Memory Games

1. Active Retrieval (The Testing Effect)

Trying to recall information strengthens memory more than passively re-reading it. This is called the testing effect.

When you flip cards in CortexQuest to match "mitochondria" with "powerhouse of the cell," you're forcing your brain to retrieve the answer — not just recognize it. That's powerful learning.

Better than: Highlighting or re-reading notes

Why it works: Retrieval strengthens memory pathways (Roediger & Butler, 2011)

2. Spaced Repetition

The spacing effect shows that reviewing material across multiple days helps retention far more than cramming.

Memory games that repeat the same topic over time naturally space out your practice, improving long-term memory.

Tip: Play the same topic a few times over several days

Why it works: Distributed practice leads to durable learning (Cepeda et al., 2008)

3. Dual Coding: Visual + Verbal Memory

According to dual coding theory, we learn better when information is processed both visually and verbally.

In memory-matching games:

- Visual: You remember card positions

- Verbal: You connect terms with definitions

- Spatial: You mentally locate answers on the grid

Combining visuals with text improves encoding and recall (Paivio, 2007)

During gameplay: You see card positions (visual), read terms (verbal), and remember spatial locations

4. Desirable Difficulty

Struggling to recall something actually improves memory, as long as you eventually succeed. Psychologists call this a desirable difficulty.

Memory games create this effect through:

- Time pressure (Time Attack mode)

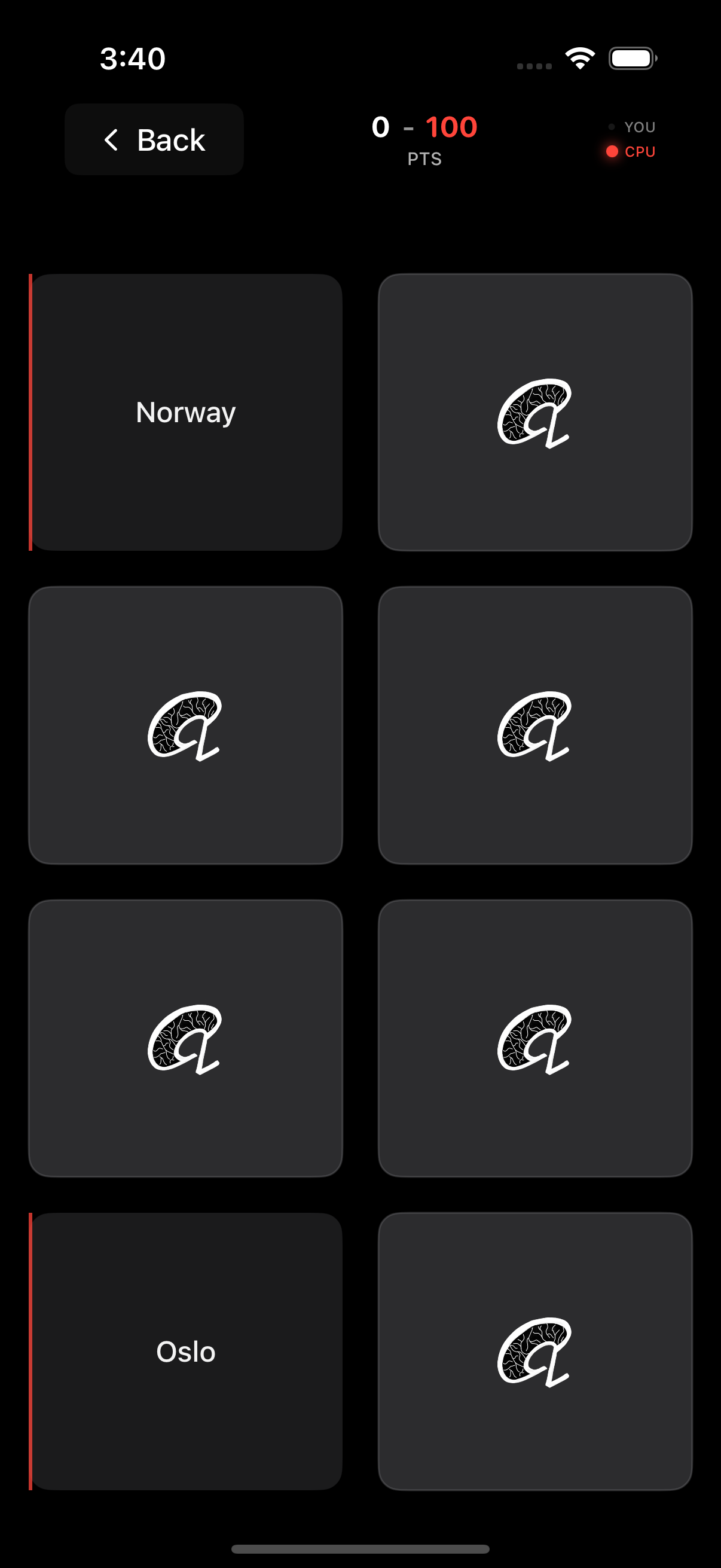

- Competitive challenges (VS CPU mode)

- Remembering card locations under cognitive load

Harder learning often leads to better retention (Bjork & Bjork, 2011)

Connecting Memory Games with Behavioral Science

If you've read Thinking, Fast and Slow or Make It Stick, you've already encountered some of these principles. Here's how popular science reinforces what the research says:

Kahneman's "System 2" Thinking

In Daniel Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow, he describes two systems of thinking:

- System 1: Fast, automatic, effortless (like recognizing faces)

- System 2: Slow, deliberate, effortful (like solving math problems)

At first, memory games engage System 2 — your slow, effortful thinking system. Over time, patterns become easier, shifting into System 1 (automatic recall).

Beware of Cognitive Ease

Kahneman warns that when something feels easy, we assume we've learned it. Memory games force you into active engagement, making them better than passive methods like re-reading.

"Make It Stick" Highlights

Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel's Make It Stick (2014) aligns with memory games:

- Effortful retrieval beats passive review

- Spaced practice beats cramming

- Interleaving topics improves flexibility

Key warning: Beware "illusions of knowing." Memory games force active recall, avoiding the trap of mistaking familiarity for mastery.

"Peak" and Deliberate Practice

Anders Ericsson's Peak (2016) shows expertise requires deliberate practice — focused work with immediate feedback. Memory games deliver:

- Clear goals: Match all pairs

- Instant feedback: Immediate card match results

- Scalable challenge: Multiple difficulty levels

Note: Ericsson studied complex skills (chess, music). The principle still applies to factual learning.

"Moonwalking with Einstein"

Joshua Foer's Moonwalking with Einstein (2011) shows memory is a trainable skill. He went from journalist to U.S. Memory Champion using techniques like the "memory palace."

CortexQuest uses a simplified version: you naturally remember card positions spatially ("chemistry term top-left, definition bottom-right").

Foer's honest takeaway: memorizing random facts doesn't make you smarter. But applied to meaningful content (vocabulary, concepts), memory techniques work.

Growth Mindset and Grit

Dweck's Mindset (2006) and Duckworth's Grit (2016): persistence beats innate ability.

- Fixed mindset: "I'm bad at memorization"

- Growth mindset: "I'll get better with practice"

Bottom line: Spaced practice over weeks works — if you stick with it. Consistency matters more than single-session performance.

What Memory Games Don't Do

While memory games can be powerful, let's be clear about their limits:

| Supported By Research | Not Supported |

|---|---|

| Learning specific vocabulary or concepts | Increasing IQ or general intelligence |

| Improving memory for studied material | Enhancing unrelated skills |

| Better retention via retrieval and spacing | Preventing cognitive decline or dementia |

| Greater engagement vs flashcards | Expanding working memory capacity |

How to Use Memory Games Effectively

Want to get real learning benefits from memory games? Follow these research-backed strategies:

1. Focus on Learning, Not Just Winning

Actually read and think about the terms — don't just memorize card positions to win quickly.

Research basis: The generation effect shows that deeper processing leads to better retention (Slamecka & Graf, 1978)

2. Use Spaced Repetition

Don't play the same topic 10 times in one sitting. Instead:

Recommended schedule:

- Day 1: Play 2–3 times

- Day 3: Play once

- Day 7: Quick review

- Week 4: Final session

Research basis: Optimal intervals from Cepeda et al. (2008) — spacing at 10-20% of retention interval

3. Start Easy, Then Increase Challenge

Begin with Practice Mode to learn without pressure. Once you're accurate with most pairs, move to Time Attack or VS CPU modes.

Research basis: Desirable difficulties work best after basic familiarity is established (Bjork et al., 2013)

4. Interleave Topics

Mix subjects: Spanish → Chemistry → Geography. This feels harder but improves learning.

Research basis: Interleaved practice produces better long-term retention than blocked practice (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007)

5. Test Yourself Outside the Game

After playing, try writing down the terms or explaining them out loud without looking at the game.

Research basis: Varied retrieval contexts improve transfer (Morris et al., 1977)

6. Combine with Other Learning Methods

Memory games work best alongside:

- Reading educational content

- Taking notes and summarizing

- Teaching concepts to others

- Solving practice problems

Research basis: Multimodal learning leads to deeper understanding (Craik & Lockhart, 1972)

The Honest Verdict

Memory-matching games like CortexQuest are legitimate tools for learning, if you use them the right way. They apply proven cognitive science:

- Retrieval practice

- Spaced repetition

- Visual-verbal encoding

- Desirable difficulty

But remember:

They help you remember facts — not become a genius.

They won't boost general intelligence, cure Alzheimer's, or replace deep study. Think of them as interactive flashcards, not miracle pills.

If you're learning vocabulary, science definitions, or geography facts, using a game like CortexQuest for 10–15 minutes a day, consistently, is likely more effective than passive review.

Just don't expect it to make you a genius. Science doesn't work that way.

References

Academic Research

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes (Vol. 2, pp. 35-67).

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society, 2(59-68).

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354.

Cepeda, N. J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J. T., & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning: A temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological Science, 19(11), 1095-1102.

Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671-684.

Morris, C. D., Bransford, J. D., & Franks, J. J. (1977). Levels of processing versus transfer appropriate processing. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(5), 519-533.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20-27.

Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2007). The shuffling of mathematics practice problems improves learning. Instructional Science, 35(6), 481-498.

Simons, D. J., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., et al. (2016). Do "brain-training" programs work?. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17(3), 103-186.

Slamecka, N. J., & Graf, P. (1978). The generation effect: Delineation of a phenomenon. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 4(6), 592.

Popular Science Books

Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. New York: Scribner.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.

Ericsson, A., & Pool, R. (2016). Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Foer, J. (2011). Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything. New York: Penguin Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Ready to Put This Research Into Practice?

Try CortexQuest and use these evidence-based strategies to maximize your learning.

Start Learning with CortexQuestRemember: Consistency over intensity • Spacing over cramming • Active recall over passive review